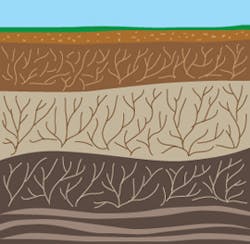

You may have more in common with the soil than you realize. Scientists in Finland have recently noted that soil macropores, or air-filled spaces within the soil, have some similarity to human blood vessels, with branching patterns that resemble our own circulatory system. Macropores allow water to infiltrate and move laterally through the soil. And just as blockages in an artery can cause problems in a human, compression of macropores can cause problems for healthy soil.

A team of researchers has been using computed tomograph scanning-CT scans, once commonly referred to as CAT scans-to investigate exactly what’s going on underground. It’s perhaps the only nondestructive way to do so; digging into the soil to see its structure, however delicately it’s done, would destroy the very features they want to observe.

The specific problem the researchers diagnosed in this case was soil compaction caused by heavy farm equipment. The effects they saw were surprisingly long lasting: Even in an area where heavy equipment was last used three decades earlier, the soil was still compacted. Even worse, they noted that the tractor-trailer originally driven over the area to compact the soil was lighter than typical farm equipment in use today. The areas tested-both those known to have been compacted and the “control” plots-consisted mainly of clayey soils, which may have more difficulty recovering once compacted than less-dense soil types.

Compaction somewhat reduced the vertical or “arterial” macropores, but it especially affected the horizontal pores that branched off from the main ones. Because most of the remaining macropores are vertical, water added to the soil tends to flow downward rather than spreading through the soil, which can affect crop growth and make the soil less productive overall. Yet farmers and people trying to revegetate in other areas, such as construction sites where heavy equipment has been used, might not recognize the reasons for decreased growth. One implication of the study is that some sort of remediation might be necessary for soils that have previously been compacted-tilling in new organic matter, for example, down to depths of more than a foot-to restore optimum productivity.

The practice of using CT scans to determine soil condition isn’t exactly new; the first CT scanners for medical use were developed in the late 1960s, and by the early 1980s a few scientists were using them to determine water content and bulk density of soils. A 1991 report from the University of Minnesota’s Water Resources Research Center summarizes some of the earlier studies and the authors’ own experiments. Their focus was on how water infiltrates and percolates through soil, and particularly how chemicals like pesticides might travel through the soil to reach groundwater-a potential source of drinking water in many places.

Are you aware of-or are you using in your own projects-technologies that were originally developed for other purposes? Tell us about it at www.erosioncontrol.com.

About the Author

Janice Kaspersen

Janice Kaspersen is the former editor of Erosion Control and Stormwater magazines.